Anatomy and Function of the Horse’s Stomach – And Why So Many Horses Suffer from Gastric Ulcers

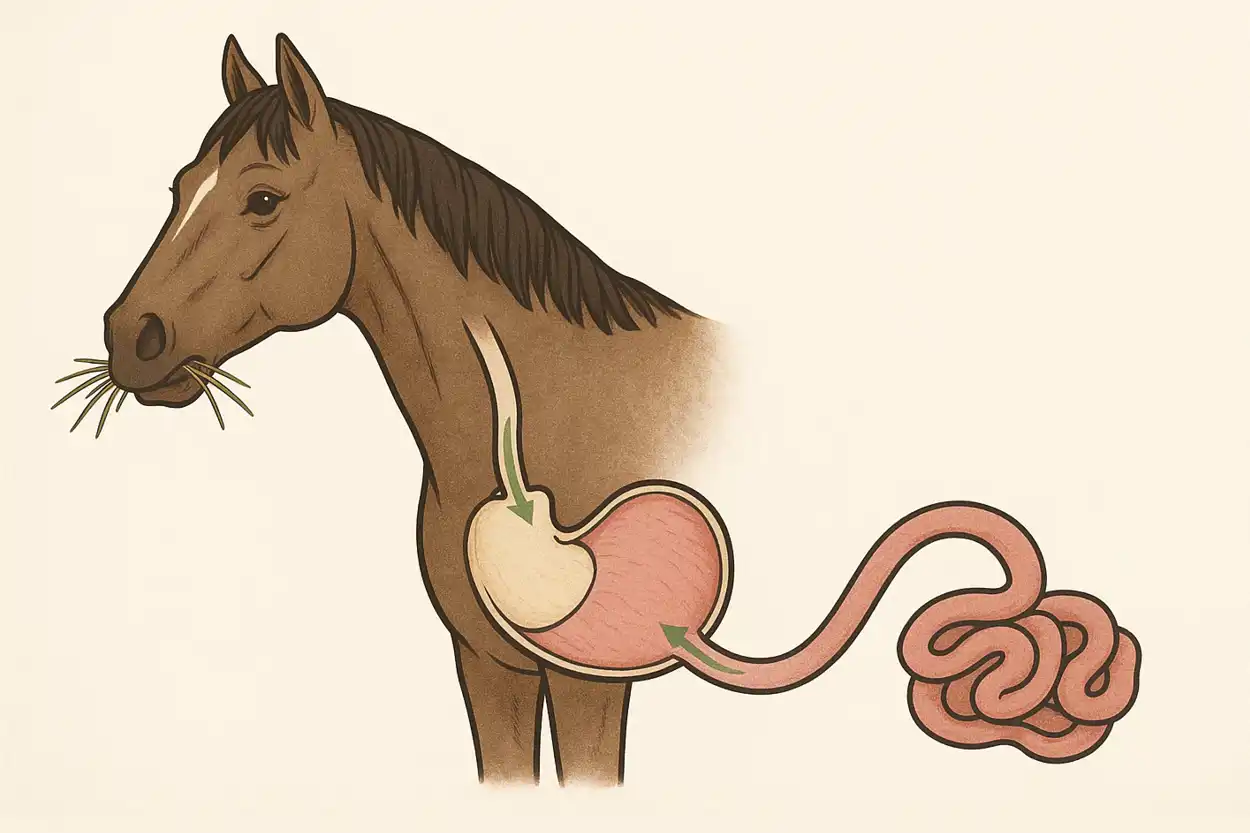

The Anatomy of the Horse’s Stomach

The horse’s stomach is a relatively small, L-shaped organ with a capacity of only about 10–15 litres – surprisingly little for such a large animal. Food enters the stomach via the oesophagus, where it mixes with gastric juices and begins the digestive process. A unique feature is the two-part division of the stomach lining:

- Pars non glandularis (non-glandular part): This upper third does not produce gastric acid and has little protection against acid.

- Pars glandularis (glandular part): Produces stomach acid and is protected by mucus and bicarbonate.

Between the two sections lies the Margo plicatus, a key anatomical border and a common weak point for ulcer development.

Function of the Stomach

The stomach’s main tasks include:

- Mixing food with gastric juice via muscle contractions

- Acidifying feed with hydrochloric acid (HCl) to kill pathogens

- Breaking down proteins using the enzyme pepsin

Important to note: Unlike humans, the horse’s stomach produces gastric acid continuously – even when the horse isn’t eating.

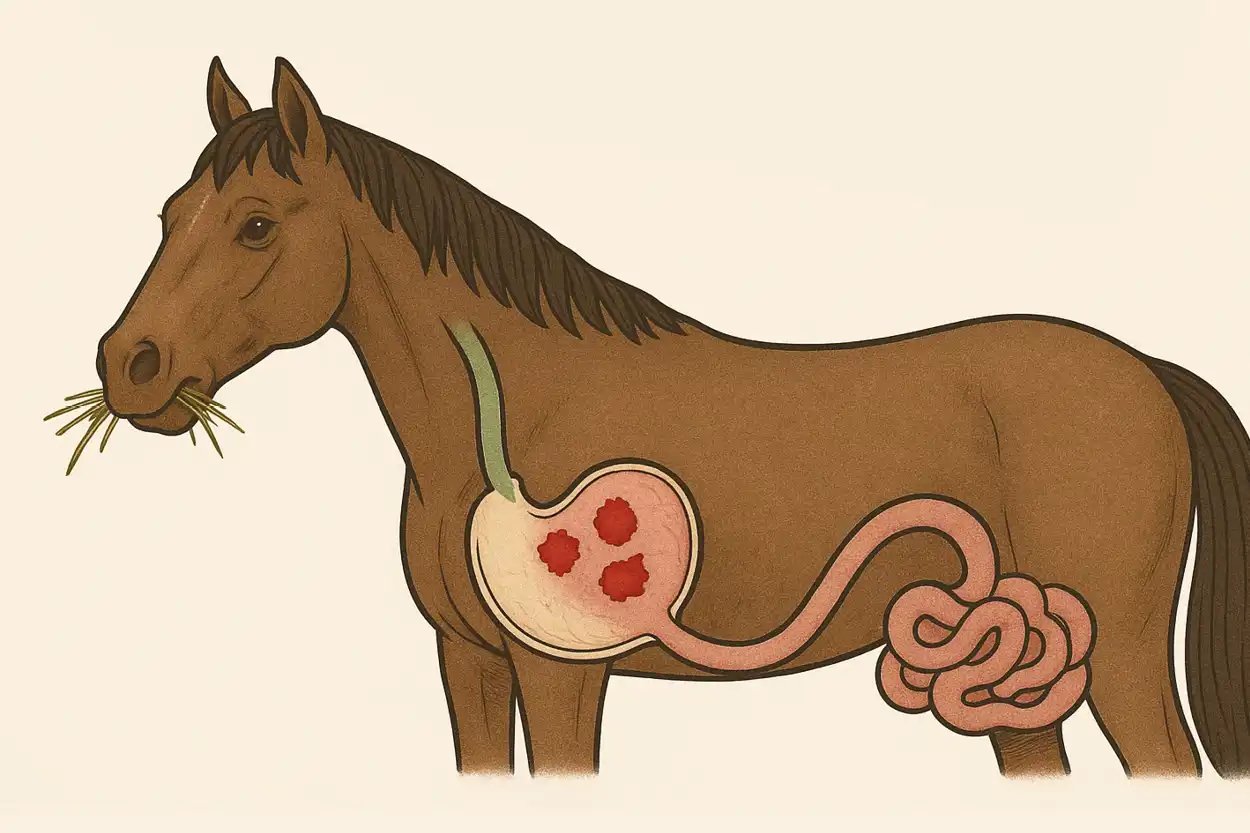

Why Do Gastric Problems Occur? – Equine Gastric Ulcer Syndrome (EGUS)

EGUS is a common yet often underestimated condition in horses. It involves inflammation or ulcers of the stomach lining caused by an imbalance between acid production and protective mechanisms.

Causes:

- Feed gaps over 4 hours

- Insufficient roughage intake

- High levels of concentrate feed (grains, sugars)

- Stress (housing, training, stable changes)

- Medications (especially NSAIDs, corticosteroids)

- Poor feed quality

If feed intake is too low, saliva and fibrous material are missing as natural buffers. The acid then attacks the unprotected lining of the non-glandular part – leading to irritation, inflammation, and ulcers.

Feeding: A Central Role

Roughage as a Protective Factor

Forage such as hay or grass should always be available – or at least provided often enough to prevent feed gaps of more than 3–4 hours.

Benefits:

- Plenty of saliva = more bicarbonate for buffering

- Loose structure = good mixing with gastric juice

- Fast stomach passage = acid moves along quickly

Concentrate Feed as a Risk Factor

Grain-based feed is fermented in the stomach, producing lactic acid – another source of acid. Concentrates are also dense and poorly mixed with stomach acid, staying in the stomach longer – ideal conditions for acid-related damage.

Risky Feed for Sensitive Horses

| Feedstuff

|

Risk

|

|

Apples

|

High in fructose & acid → lactic acid formation

|

| Bananas

|

Very high in sugar

|

| Citrus fruits

|

High acid content |

| Dry bread

|

White flour, high starch → strongly acid-forming |

| Treats

|

Usually high in sugar & grain

|

| Spicy foods

|

Irritating to stomach lining, especially in sensitive horses

|

Tip: Small amounts may be safe for healthy horses – but should be strictly avoided in “ulcer-prone” horses!

Stress – The Invisible Trigger

Stress reduces stomach blood flow and suppresses mucus production. Common stressors:

- Frequent transportation

- Competition-related pressure

- Unstable herd dynamics

- Food-related aggression or rank conflicts

- Stall housing with limited movement

Minimising stress through species-appropriate management is crucial for ulcer-prone horses.

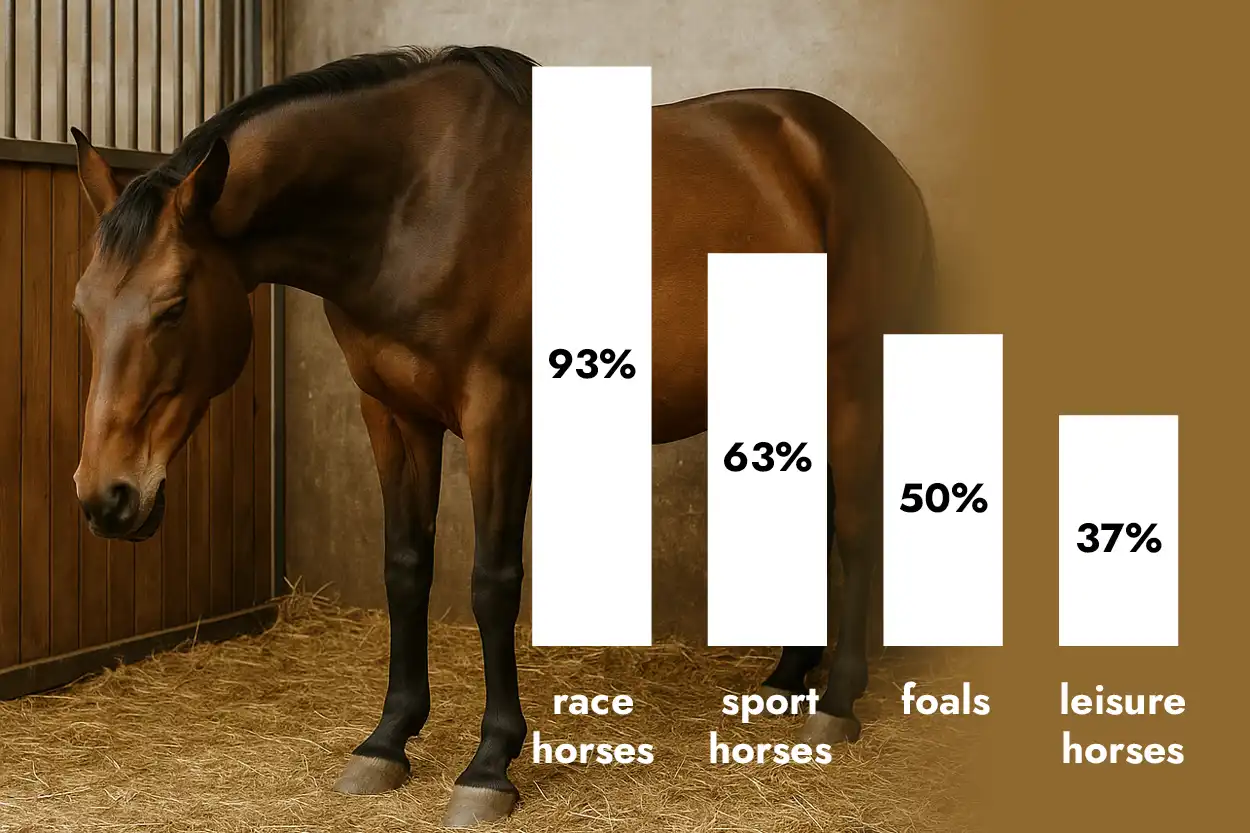

Prevalence – An Underestimated Epidemic?

A study (McClure et al., 1999) revealed alarming figures:

- 93% of racehorses

- 63% of sport horses

- 50% of foals

- 37% of leisure horses

…showed gastric lesions during gastroscopy. The actual numbers may be even higher, as many symptoms are non-specific (e.g. poor performance, girthiness, dull coat, yawning, chewing without food, colic tendencies).

Conclusion: How to Keep the Horse’s Stomach Healthy

- Provide roughage ad libitum (especially hay)

- Avoid feed gaps > 4 hours

- Reduce or replace concentrate feed

- Minimise stress – improve herd housing

- Regular check-ups for sensitive horses

- Use gastric protection when giving medications